What do astronomers actually do?

It was October 2022, when, after several nights of long working hours, we managed to put together an observing proposal for the recently launched James Webb Space Telescope (or JWST for short). We wanted to test whether the emission from Ultraluminous X-ray sources — we’ll get there in a second — was isotropic or, as some theoreticians had suggested, ‘beamed’. An idea for an experiment using JWST infrared detectors had been in mind for some time, but I lacked the expertise to implement it. It was shortly before the JWST proposal deadline when I finally met someone with the know-how to implement the experiment I had in mind.

While our proposal was not accepted, some interesting ideas came out of the painful process of preparing it. Often times you need to ‘simulate’ beforehand what you predict you are going to ‘see’ and how you’re going to analyse it, and it was thanks to this process that we realized we already had all the pieces to carry out our experiment: there was some existing data in the archives from ground-based observatories, which although not perfect, in principle could suffice for a preliminary study, and I had finally found the right collaborator for the project — all we had to do was to sit down and get to work.

“Let’s do this on the ‘side’; it’ll be a quick, 3-month thing” — my colleague told me excitedly. It took us about a year from start to publication — a reminder of what I already knew from reading Daniel Kahneman’s “Thinking, Fast and Slow”: that we, humans, are terribly optimistic when it comes to estimating the length of a project.

Astronomy is a peculiar science in at least two fronts: for one, we cannot really carry out ‘experiments’ on Earth because we cannot reproduce many of the conditions found in space (think vacuum, temperature, magnetic fields, etc) — hence it is said that astronomy is an ‘observational’ science. But more relevant here, is that, except for the nearest astronomical sources, we are limited to observe things through a single, viewing direction. We cannot answer, say, ‘How does the Crab nebula look from the side?’ We can only know how the Crab nebula looks like from Earth. We also cannot navigate to a given system, observe it from another angle, and see whether the amount of light emanating from it is the same in all directions — as you would do with, say, a streetlight.

This uniqueness of viewing angle inherent in astronomy makes it hard to know whether a given astronomical source is isotropic — meaning, whether it radiates the same energy output in every direction. And unless we contact some aliens asking what they see from their point of view, we have to get ingenious.

Asking the clouds

So how do we, then, determine whether a given astronomical source is isotropic? To answer that, let me first talk about an astronomical object that may be more familiar to you: the Moon.

Now suppose you wanted to know whether the Moon is an isotropic source — meaning you’d like to know whether the Moon radiates spherically ‘outwards’ so to speak, like a star or a lightbulb — or whether it is an anisotropic source — like a ‘beam’ of light, like you would see a car’s headlight or a lamp pointed towards Earth. In reality, the Moon doesn’t emit any light of its own (at least in the visible) — its glow is due to sunlight reflection, but let’s ignore this fact for the sake of simplicity. If you were to observe the Moon on a cloudless night from your humble, limited, terrestrial perspective, you’d have no way to tell these two hypotheses apart. This point is brilliantly illustrated in a presentation by Prof. Philip Kaaret (link for the specific point up to minute 42).

But now imagine, there were some clouds around it, like in the picture. These clouds are obviously on Earth’s atmosphere, but let’s just imagine for a second, these clouds were on the same plane as the Moon, or at least located at a similar distance. If that was the case, then the simple fact that these clouds are reflecting some of the Moon’s light already tells you the amount of light emanating in the direction of these clouds is similar to the one you observe directly — chances are, then, the Moon is close to an isotropic emitter. Hence, by studying the re-emitted light by clouds like this in detail, one can attempt to determine whether they ‘see’ the same moonlight as you observe along the line of sight.

Ultraluminous X-ray sources

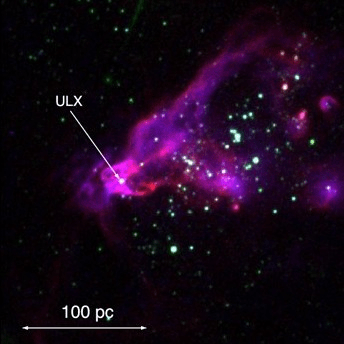

The object we actually want to know whether is a beam of light is not the Moon, but something orders of magnitude more luminous and fascinating — an Ultraluminous X-ray source. It is, in fact, not one but two objects: a compact object, i.e. a black hole or a neutron star — we still aren’t sure — swallowing a regular star in a binary system (like the Moon-Earth system). In such systems, the gas from the donor star swirls around the black hole or the neutron star, forming an accretion disk, where the gas is accelerated to relativistic speeds and heated up to about 10 million degrees Celsius due to the strong gravitational potential. The emission we measure from these systems is mainly due to this hot, glow from the accretion disk, and due to the high temperatures, the emitted photons are highly energetic, mainly concentrated in the X-ray band of the electromagnetic spectrum, hence why they are known as ‘X-ray binaries’. These systems are too far for us to ‘resolve’ them — we mostly see them as ‘point-like’ sources, like you would see a very distant streetlight or Jupiter in the sky.

In extreme cases, when the compact object is swallowing the star at a much faster rate, the disk glows 50–500 times more luminous than in standard X-ray binaries — we term these Ultraluminous X-ray sources (or ULXs for short). I wrote extensively about these systems in a previous post.

Are we seeing light beams?

But some astronomers are not convinced; they think the emission from the accretion disk in ULXs is not as bright as we think it is, they think we are being fooled by assuming the emission to be isotropic; they argue instead that the emission is more like a beam, and that by assuming the emission to be isotropic — like for a star — we are overestimating the amount of light (or energy) being released.

The reason why it is important to know is that in many respects, astronomy is about following the flow of energy: we want to know where or how energy is produced, how it is released and where it ends up. If ULXs are as bright as we think they are, it means their radiative output is enormous: they will rival the output of the accretion disks around some supermassive black holes, enough to shape or alter some galaxy properties. On the other hand, if they are beamed, it means their radiative output is diminished — they are less important in the grand scheme of things. Moreover, if we are able to pin down the exact radiative output, this will also help us know whether at the centre lies a black hole or a neutron star, another open question about these systems.

An astronomical experiment

So we set out to test this ‘Moon-cloud’ idea. In a previous work, we discovered an extended gas cloud being irradiated by the UV/X-ray light emanating from the accretion disk of a ULX. We know these clouds are located in the same galaxy as the ULX due to their redshift, so we know their distance is about the same as the ULX — in this case about 13 million lightyears. Hence, this system presented the perfect opportunity to carry out our experiment: we had spectroscopic data from the ULX itself (the ‘Moon’) and we had some Integral Field Unit data from the Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer from the nearby gas (the ‘clouds’). All we had to do was compare whether these clouds were ‘seeing’ the same light as observed directly from the ULX.

To do that, we used an astrophysical code called ‘CLOUDY’ to recreate the emission expected from gas clouds with varying geometries (e.g. density, distance to the ULX, extent, etc) when illuminated by the radiation field of the ULX (which we had measured using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, ESA’s X-ray XMM-Newton telescope and NASA’s NuSTAR telescope high-energy data). In essence, CLOUDY allows you to simulate the ‘response’ or re-emission of a gas cloud when irradiated by a light source (when ‘photo-ionized’). For the reader interested in the technical details (otherwise feel free to skip to the next paragraph), CLOUDY will solve all the radiative transfer equations, taking into account things like the photoelectric effect, recombination of the gas, Compton scattering, etc, based on the gas density, atomic elements and input photon source. The code will calculate self-consistently the temperature and ionisation state of the atoms in the gas, from which the ‘spectrum’ or light emitted by the gas can be inferred.

In this way, all we had to do was to compare the output from the CLOUDY simulations to the emission measured from the gas clouds using the existing data: If these two were similar, then we can conclude the clouds see very similar emission as we see directly — the ULX is close to isotropic. If on the other hand, the output of the simulations is much brighter than what the clouds themselves emit, then we may conclude that the clouds are seeing a lesser amount of light than we see along the line of sight — the ULX is anisotropic.

What we found was that at least in the UV band, where our observations were more sensitive, the clouds see about 4 times less light than what we see directly from the ULX, meaning there is indeed a certain degree of anisotropy, although less than implied by some theoreticians. We think that the colder, UV emission, may be emitted from regions further from the black hole, in a sort of outflow shrouding the accretion disk, which results in a quasi-isotropic emission. Instead, it is possible that the high-energy emission (X-rays) coming from closer to the black hole (or neutron star) are beamed by a larger factor.

Such studies are undeniably quite uncertain. First, we do not really know the exact geometry of the clouds, and we need to make some assumptions within our simulations: for instance, that they have uniform density and are plane parallel. We are working on improving our methods, allowing for more complex density profiles, as well as taking into account the 3D structure of the clouds. Further, the atomic transitions probed by the optical observations afforded by the Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer at the Very Large Telescope are more readily sensitive to UV photons. To test the anisotropy of the X-ray emission, we need astronomers’ favourite toy.

The fierce fight to observe with JWST, the astronomers’ new toy

Unfortunately, our JWST observing proposal was not accepted. Competition to get data is fierce — the last call for proposals broke the record of most requested telescope time ever, and the over-subscription factor was 9, meaning there was 9 time more requested time than available for observing. Stop for a second and think what that means… can you imagine there being 9 times more demand for iPhones than Apple could produce in a year?

This means that even great proposals with no obvious flaws get inevitably turned down. But the upside is that the scientific return is maximized: only those scientific cases, those observing proposal that promise to deliver the greatest return on science, get approved, and their targets observed, ensuring the most efficient advance of astronomical science.

What makes the JWST so interesting for our case is that not only does it provide observations free of atmospheric distortions and thus with a much finer spatial resolution — allowing us to resolve the clouds more precisely, pinpointing exactly where it is that they are emitting — it also observes in the infrared band, where atomic transitions of elements that have lost several electrons occur (for instance we can observe atomic transitions of Ne VI or Mg VII, that is, from Neon and Magnesium atoms that have lost 5 and 6 electrons, respectively). In order to get an atom deprived of so many electrons, it must have undergone photoelectric effect with high-energy photons — meaning, these atomic transitions are good tracers of X-rays, which is precisely where we expect the emission to be more strongly anisotropic. For that reason, this year we will try again to request data from the JWST.

If these observations are granted, it may be possible that we will settle the debate as to whether the emission from these mighty systems is indeed as mighty as it appears to be, or rather, we might be able to show that indeed we are being fooled by our limited perspective and projection effects.

Link to the journal articles.

Leave a comment