My main line of scientific research focuses on understanding the nature of the extragalactic Ultraluminous X-ray sources. These systems were discovered towards the late 70s when humankind had finally the technology to ‘resolve’ the X-ray emission in external galaxies. What they found puzzled astronomers at the time: they discovered that in the outskirts of each of these galaxies there were one or two abnormally bright sources. This discovery was puzzling for at least a couple of reasons. First, we obviously know of very luminous sources in the X-rays; the most luminous being the accreting supermassive black holes that reside at the center of (nearly almost) every galaxy (also known as Active Galactic Nuclei). But these massive black holes weigh billions of times the mass of our Sun, so they always sink to the center of the galaxy, which is where we find them. Secondly, while we do observe X-ray sources lurking in the outskirts of our own or other galaxies — such as flaring stars, supernova remnants, or tiny black holes or neutron stars devouring their companion stars— the discovered sources were hundreds of times more luminous than any of these objects. So they nature was puzzling at the time, but another piece of evidence soon set astronomers in the right direction: they were found to be persistent and highly variable, the signatures of a black hole devouring its companion star.

Two theories were proposed at the time to explain their abnormal luminosities, both of which can simultaneously occur in nature (i.e. these two theories are not mutually exclusive).

Heavy Black Holes

We know the luminosity radiated from accreting objects is proportional to their mass — heavier black holes have stronger gravitational pulls, and are able to generate more radiation from the accreting gas. Thus, an easy explanation was that these were simply heavier black holes than typically observed in the binary systems dispersed throughout our own and other galaxies, but lighter than the supermassive black holes found at the center of galaxies. These would then represent a new “kind” of black hole, a very elusive form of black hole which we actually have very little evidence for. Astronomers refer to them as Intermediate Mass Black Holes, because they sit between those tiny black holes formed after stars die and go supernova, and those that presumably formed early in the Universe and grew to become the monster supermassive black holes we observe in the present day.

A handful of ULXs might indeed host Intermediate Mass Black Holes. But it is agreed that only a minor fraction of ULXs are powered by an accreting, heavy black hole, although identifying more of these exotic objects in an active area of research in astrophysics.

The Brightest Compact Objects

The second theory is that it is not the mass that is heavier in these systems, but the rate at which the companion star is “feeding” or transferring mass to the black hole. This fast-paced mode of accretion had been theorized as early as the 70s but whether it could be sustained or operated in nature at all was not completely clear. Today we know the extreme luminosities observed in most ULXs come from this process. There are other systems where this phenomena is also observed, like when a supermassive black hole tidally disrupts a wandering star, but a peculiar feature of ULXs is that this extreme accretion process seems to be sustained. Thus, much of the research revolving around ULXs focuses on understanding this process and the energy released back into the environment through it.

Now that all more or less good until in 2014 researchers discovered pulsations using NASA’s recently launched high-energy NuSTAR telescope. If you’ve ever heard of pulsars, yep, that’s it: the presence of pulsations can only be produced by a hard surface, a lighthouse of sorts, and undeniably indicated the accretor was a neutron star. This was a big surprise in the field and since then, pulsations have been discovered in about 7 more ULXs, but they remain highly elusive!

The questions I try to answer with my research are therefore:

- What is the nature of ULXs, how many host tiny or heavy black holes, and how many host neutron stars?

- If many host neutron stars, but we cannot detect pulsations, how can we go about identifying them? And why we do not observe these pulsations?

- How much energy is liberated in the accretion process, in the form of radiation and powerful outflows?

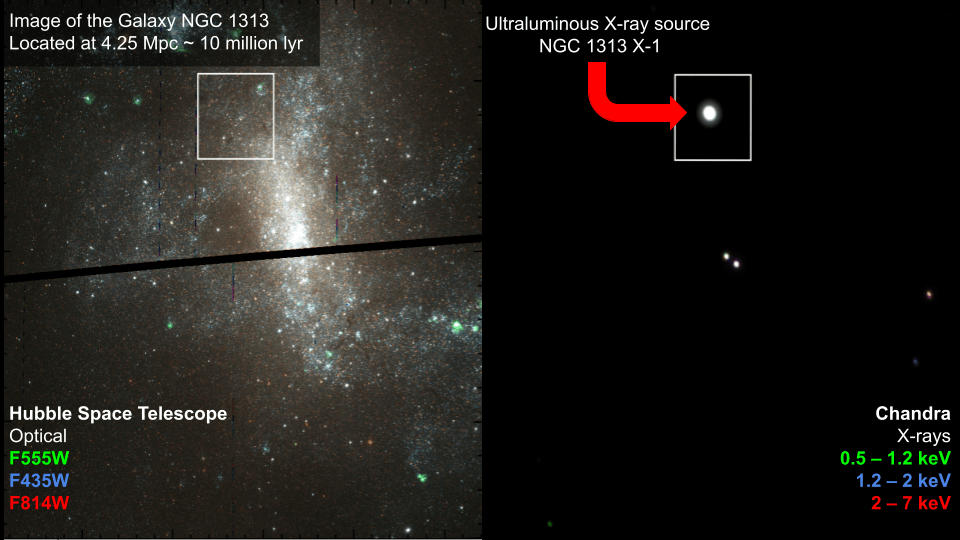

To do that, on the one hand I use data from space-borne observatories in X-rays, such as the European Space Agency’s X-ray Multi-Mirror-Newton, NASA’s NuSTAR and the Chandra X-ray observatory, and in the IR/optical and UV, such as the Hubble Space Telescope, to study the light emanating directly from the accretion disk in ULXs to understand their nature.

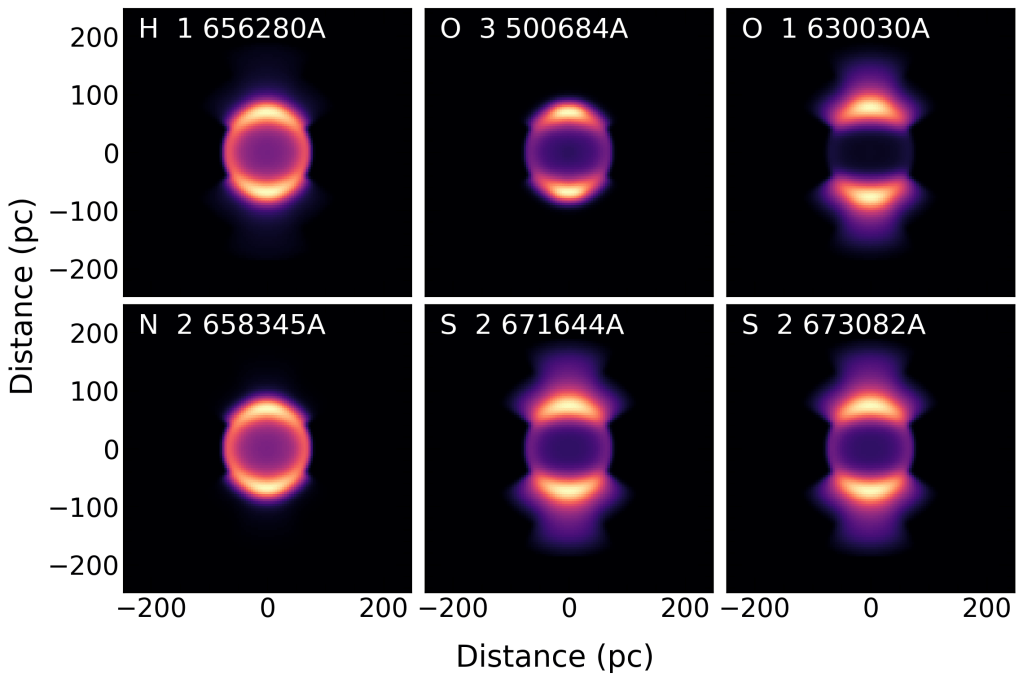

On the other hand, I use instruments known as Integral-Field Unit Spectrometers from ground-based observatories, such as the Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer at one of the 8-m units at the Very Large Telescope or MEGARA on the 10-m Gran Telescopio Canarias, to study the ionized nebulae produced around them such as the one shown below. With these studies I try to quantify how much energy ULXs release onto the environment. You can read more details about it in this entry of my blog.

At the moment, I am trying to quantify how much radiative energy is released in the environment by these mighty accretors. To do that, I’m investigating how the interstellar medium would “glow” in various atomic transitions when irradiated by the accretion disk of a ULX by producing maps as the one below. The idea is then compare these simulated, nebular models to observations of actual nebulae to try to constrain what accretion disk model from the ULX best matches the data. For more details, have a look at this entry of my blog.