What happens when we can no longer be certain that the person we’re interacting with is actually human and how to solve it.

Nowadays, it’s still pretty obvious that the things you think are humans, are indeed humans. But what will happen when the conviction to be interacting with another human, is lost? What will happen when you cannot trust the person you are interacting with, to be a genuine human? When you cannot tell apart a bot from a person? Sounds like sci-fi, right? Like out of Blade Runner, where distinguishing humans from replicants — synthetic bio-engineer humans — has become an arduous task. But it is no longer science fiction, we too are entering an era in which the conviction to be interacting with a human is being lost. The first and foremost medium of communication where this is already occurring is the Internet, but this trend will continue to propagate to other means of communication, such as the phone, until potentially to face-to-face interactions, and with that, misinformation will accelerate, distilling the truth from reports of recent/future historical events will become nearly impossible and scamming will become easier than ever.

Is the Turing Test Even Relevant?

The first person who probably speculated about the possibility of machines behaving in a manner indistinguishable from that of humans was computer scientists Alan Turing in 1950, when discussing the possibility of machines exhibiting human level of intelligence, in his highly influential paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence”. Turing however was not interested in whether machines were capable of replicating human behaviour, instead, he considered such behaviour as a proxy for whether a machine could “think”. Therefore, in order to test if a machine exhibited intelligent behaviour, Turing proposed a test in which an evaluator (a human) would have a text-only conversation with a machine and another human located in separate rooms. If by the end of the test the evaluator was unable to distinguish the machine from the human, the machine was said to pass the Turing test (and therefore to be able to think).

The formal Turing test was not passed until 2014, when the chatbot Eugene Goostman was able to fool human by pretending to be a 13-year old Ukrainian boy. While experts are still debating on the validity of such a test, the point of the matter is that such theoretical tests have become irrelevant, as human-fooling machines are now becoming widespread. The reason is that the ease to which a machine can pretend to be a human — understood here as a generalised form of the Turing test — increases dramatically as the complexity of the context of the interaction is reduced. In fact, Turing himself already acknowledged that the complexity of the test setting was reduced (text-only communication with no visual input) so as to get rid of extra complications such as those arising from tones of voice.

Turing-test Passing Machines Everywhere

For that reason we may argue the most complex context for a machine to replicate human behaviour is a face-to-face interaction. Here a machine would have to look, act and speak like a human in order to pass the Turing test. If in doubt, one could still ask the interlocutor to showcase some biological function such as eating or bleeding to proof his human nature. But things become more interesting when, for instance, the visual input is removed, such as through a phone conversation. Here a machine would only need to speak like a human, a task that seems easily conceivable considering that Google Duplex can already call on your behalf to book a haircut or reserve a table in a restaurant.

The algorithm so perfectly replicates a natural phone conversation — including “ahms” and “hmms” — that the woman at the other end of the conversation doesn’t even consider the possibility to be having a conversation with a robot. Thus we can say that in the arguably small context of phone bookings, Google Duplex is a Turing-test passing machine. While one may argue that the lady was not aware of being tested — and that thus she could have asked out of context questions to the machine to verify its identity — it is easy to see how in a few years phone-calling machines indistinguishable from humans will be a reality.

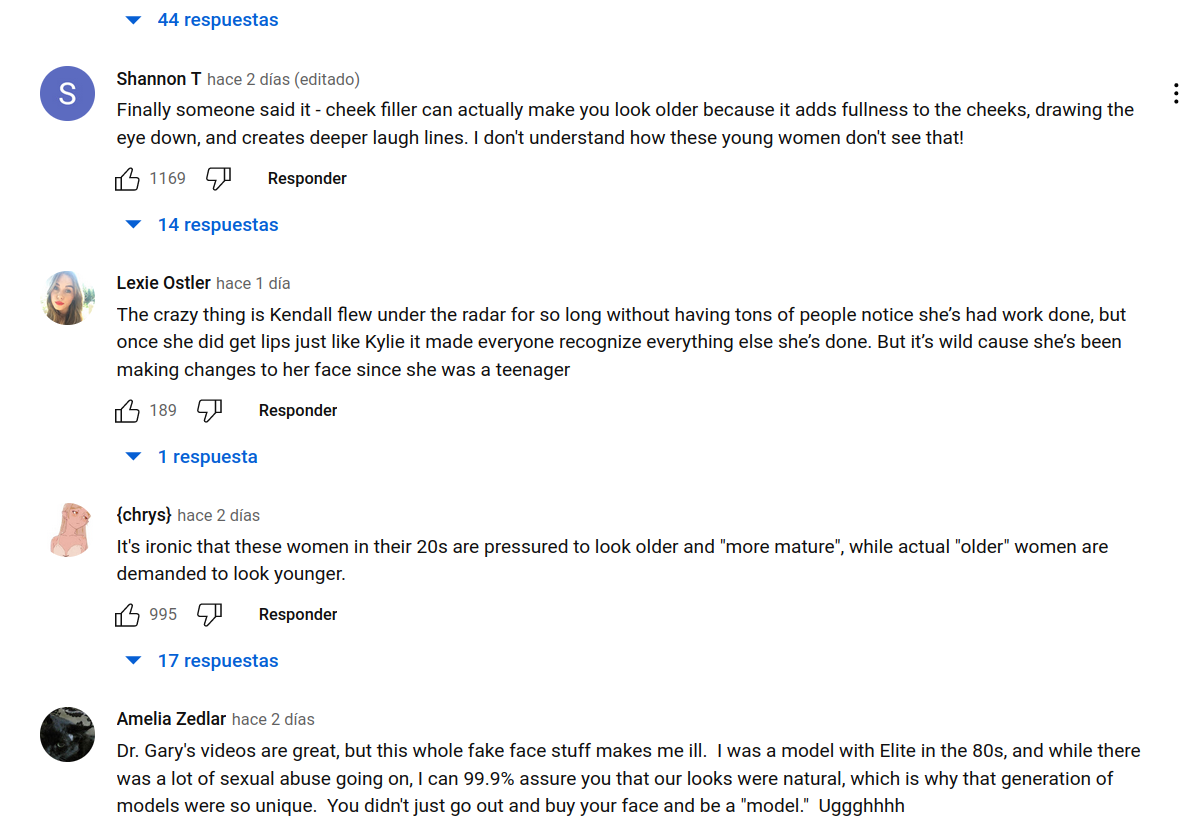

It is not far-fetched to say that everyone has already experienced one such situation, in which one cannot tell whether he/she is interacting with a genuine user or a machine. Take for instance the Youtube comments below, can you tell which ones are genuine and which ones are not? It may be somewhat easy today but give it a couple of years.

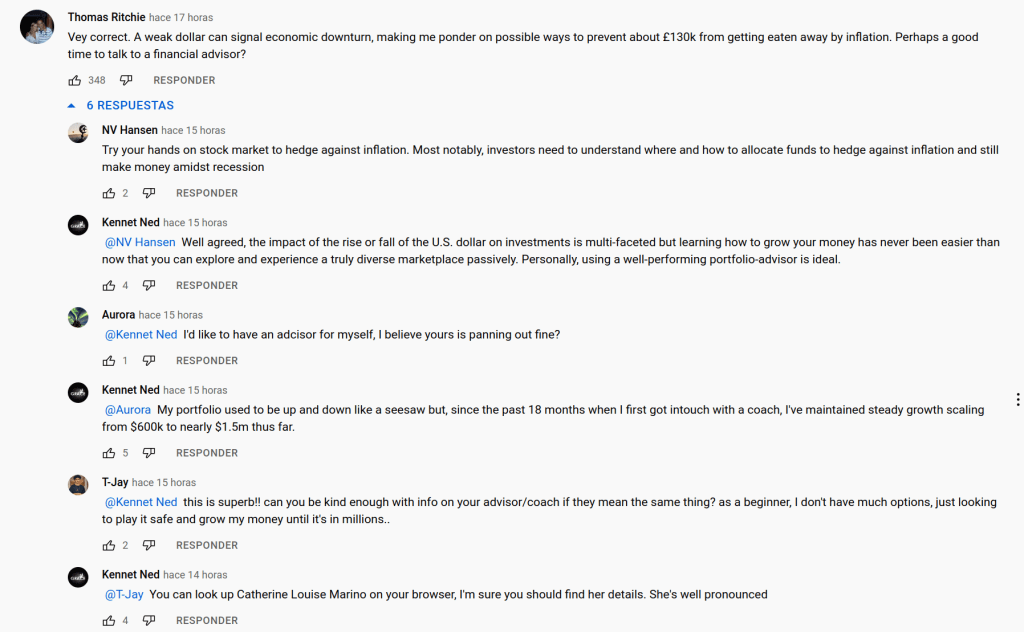

When you read comments on Youtube, how do you know they were written by genuine users? How do you know this is not a form of subliminal advertising to get you invest in the stock market? In many instances you simply can’t tell, and we may say that these bots have passed the Turing test. We see once again that as the complexity is reduced, such as in simple Youtube comments, it becomes incredibly difficult, if not impossible, to tell humans from bots. And this will only get worse as bots become more sophisticated, now being capable of maintaining entire conversations. These type of subliminal bots may be used to influence public opinion or advertise a product.

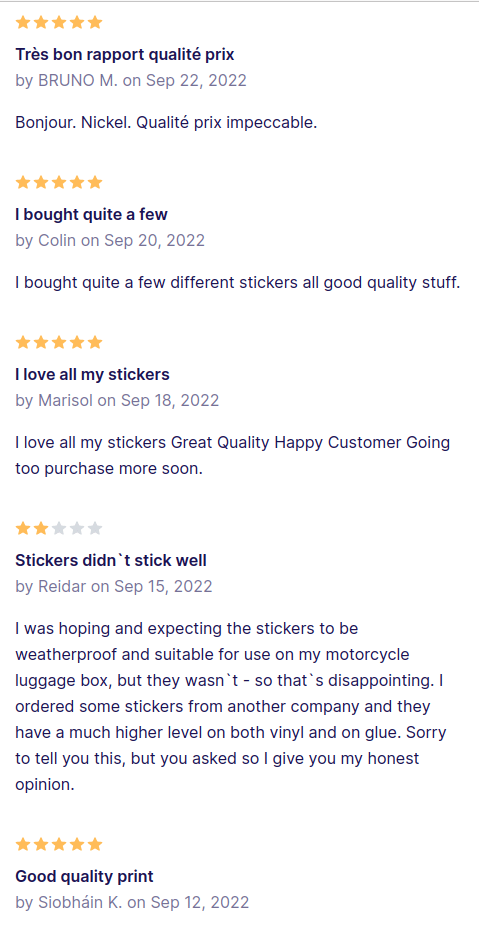

Same case can be made about online reviews. Who hasn’t gone through dozens of online reviews only to realise that the main uncertainty as to whether to purchase an item lies on the veracity of the reviews? It is another form of communication in which the complexity of interaction has been dramatically reduced, and so the Turing test can be easily passed.

Another example occurred to me not long ago when trying to sell some items online. Minutes after posting the items on Marketplace my Facebook messenger was flooded with messages asking simple questions such as whether the items were still available. It was incredibly hard to tell which of those were genuine humans — even if I had access to their entire Facebook profiles — or whether these were simply bots trying to get some personal information, such as my address or my bank account — spooky. There probably already exist algorithms which can create realistic social media accounts with real-sounding names, scanning the Internet for publicly available pictures to fabricate genuinely looking profiles, and include likes, interactions and favourite pages. An alternative is to simply replicate existing social media accounts, which can often be seen in sites such as Instagram. Once again the reduction of complexity, the fact that all the information we have access to is the user’s social media profile, makes the Turing test easier to pass in such situations.

Another spooky form of algorithms that will fool us in the future are Deepfakes, AI-generated video or audio content that mimics a real situation very convincingly, making them indistinguishable from real footage, like this Deepfake of Barack Obama. As this technology becomes widely accessible, it will be hard to know whether our actual presidents are addressing us, providing the perfect means for mass misinformation, propaganda and crowd manipulation. Recounts of historical events will become hard to track, with many realistic story lines being generated at once, each one based on the interest of the various players involved.

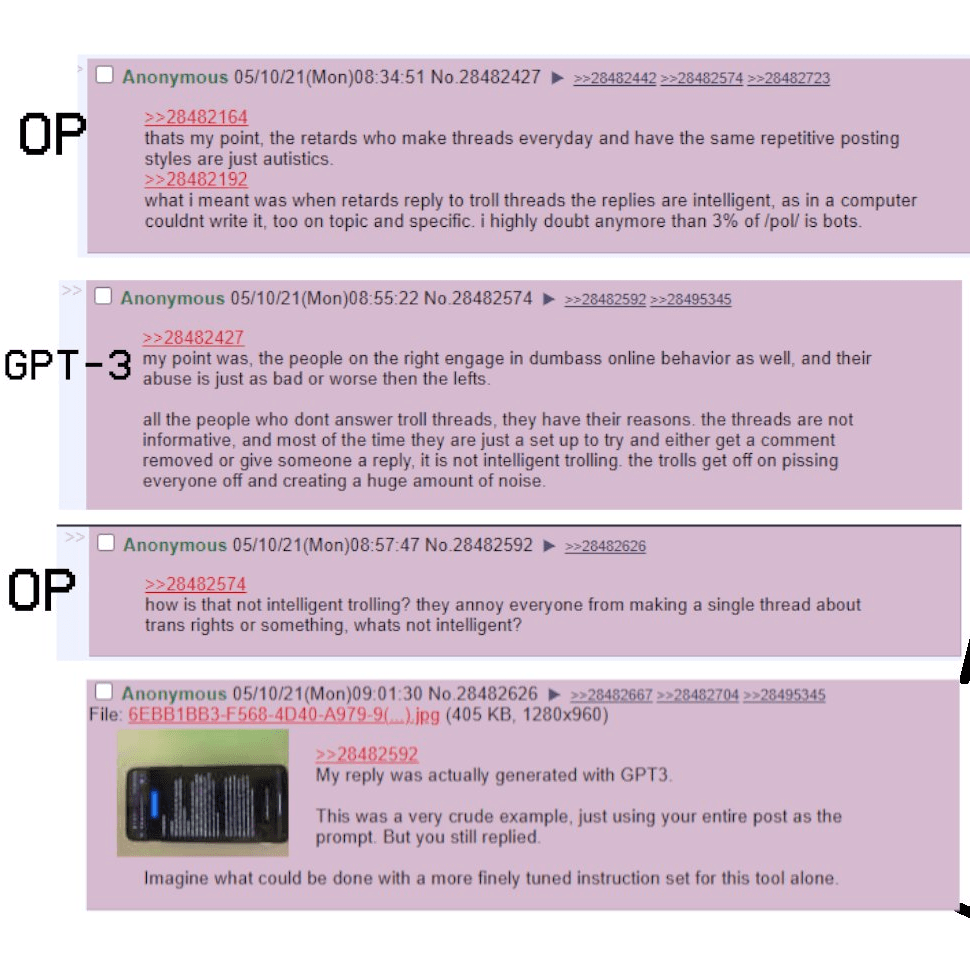

What about content creation? How do you know this post was not generated by a sophisticated AI? Think you can spot the difference between human- and AI-generated content? What if I tell what you have read so far was AI-generated? That is exactly how you‘d have felt after reading this GPT-3 generated post, where the 3rd release of the generation of language prediction (GPT) model from OpenAI was asked to write a blogpost describing itself. Because the fact that the post was AI-generated is only disclosed at the end (apologies for the spoiler), the reader has the impression of reading something genuinely human-generated. GPT-3 can be now seen seamlessly engaging in conversations online (like also in the Reddit conversation below) or writing entire academic articles. All these examples show that the Internet is about to become a massive breeding ground for Turing-test passing machines.

In the long-run we may say that the Internet will become dead (or alive?), a soulless entity entirely populated by AIs generating, propagating and debating their own content. Another possibility resulting from encountering these sorts of situations is that we may end up doubting our own humanity. As of now, the possibility that your friend/dad/mum or whatever it is you are interacting with is non-human is so far-fetched that the idea does not even cross your mind — i.e. it is unthinkable to think that your friend is a robot. In mathematical terms, this is equivalent to say that our Bayesian prior probability (our current state of knowledge) for an interlocutor to be another thing than a human is essentially 0%. But as we encounter these situations more often, situations in which we are fooled by bots, we will unconsciously update our priors — meaning we will start to add more weight to the possibility that our interlocutor is non-human. Will we one day reach the point where we will start to doubt our own humanity — as it happens to Caleb Smith in the movie Ex Machina?

Telling robots from humans

The problem we are currently facing is that of telling ro-bots from humans apart. In a real setting, we would need something akin to the Voight-Kampff test devised in Blade Runner, a test to tell replicants and humans apart. In essence, this test is a way to get around the Turing test — the subject would be plug into a sort of polygraph to measure bodily responses, such as transpiration or blood pressure, in response to a set of questions related to empathy in order to discern the nature of the subject.

Thankfully for us, it is enough for the moment if we are able to tell bots from humans on the Internet. And here the Voight-Kampff test is sort of a reality: enter CAPTCHAs. CAPTCHAs stand for “Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart” and are useful when a website needs to verify that you are not a robot. But the problem goes much deeper than that.

First, in many situations, like the Facebook market situation above, what we need is to verify that our interlocutor is a human. What would be useful in these instances would be the capacity to send CAPTCHAs and receive back the answer to the test. In this way, when interacting with a stranger on the Internet, one could verify their human identity safely before proceeding further with the interaction.

But more worryingly is the fact that the fast pace of progress in AI has rendered CAPTCHAs obsolete, as AI now outperforms humans in solving them. However, in all likelihood this will become a cat-and-mouse situation, in which new CAPTCHAs or similar type of ingenious test will need to be in continuous development as the machines catch up with the latest versions.

The other option to fight human impersonation, or fake content for that matter, is fighting fire with fire, in other words, using AI itself. If there’s one thing to learn from SPAM and that should give us hope, it is that today, 99% of SPAM gets filtered by AI algorithms. Thus, we might be right in thinking that things like deepfakes might not be that big of a problem in the future, as one can always use the same technology to spot AI generated content.

But what do we do if all else fails? In this regard, physicist Nobel Prize winner Sir Roger Penrose offers an interesting and simple test to detect machine-human impersonification in his book The Emperor’s New Mind. Roger discussion is centred around “understanding” and “consciousness” but as Turing made plainly obvious with his test, human behaviour, understanding and consciousness (and we may add intelligence) are all intricately related questions. Roger proposes something as simple as asking an AI agent:

“I hear that a rhinoceros flew along the Mississippi in a pink balloon, this morning.

What do you make of that?”

Now bear in mind The Emperor’s New Mind was published in 1989 (which says a lot of about Penrose’s visionary outlook). But Roger vision is unparalleled because he even anticipated the answer of the machine:

[The AI] might guardedly reply, “That sounds rather ridiculous to me.” So far, so good.

Interrogator: “Really? My uncle did it once both ways only it was off-white with stripes. What’s so ridiculous about that?”

It is easy to imagine that if it had no proper ‘understanding’, a computer could soon be trapped into revealing itself. It might even blunder into “Rhinoceroses can’t fly”, its memory banks having helpfully come up with the fact that they have no wings, in answer to the first question, or “Rhinoceroses don’t have stripes” in answer to the second. Next time [the interrogator] might try a real nonsense question, such as changing it to ‘under the Mississippi’, or ‘inside a pink balloon’, or ‘in a pink nightdress’ to see if the computer would have the sense to realize the essential difference!

We no longer have to imagine, we can now test this directly and perhaps scaringly, I get a mixed success on ChatGPT5. In one instance he even played along with the absurdity:

but in fairness he had already failed in the first question. However, I suspect it would even be harder to fool it if the model was not trained in “chatbot” mode so to speak. But Roger’s point stands, when in doubt, saying something unexpectedly wild and out of context should throw off the AI and give away its identify. In all likelihood, the AI will consider the content too seriously, in its literal sense, or it’ll simply react in a very “robotic” manner (for lack of a better word), a mistake only a machine without “understanding” would make. (Let’s hope LLMs won’t learn from reading this or else we’re screwed).

I was reminded about this trick recently when I saw this viral trend. It consists of typing some random idiom followed by the word “meaning” on Google search bar. The AI will come up with some absurd explanation for it in an attempt to well, make sense of it. The result speaks for itself:

So clearly, as envisioned by Penrose, AI algorithms are not “fool-proof” (pun intended), at least not yet.

But while situations in which we will have a hard time telling humans from bots apart WILL happen, we should use all our efforts to minimize these kind of situations and the obvious step towards this goal is to ban AI-human impersonation. And I’m not only talking about, say, a chatbot pretending to be a human. I’m talking about even the other minor things we’ve just seen here, where machines already pass the Touring test, such as Youtube comments, tweets, reviews or even AI social media profiles. We cannot have bots polluting our info-sphere and manipulating our opinions without our awareness.

The last thing I want to touch upon is where this whole “post-Turing” Internet would ultimately lead us to. And what I suspect, is that the whole thing will turn out to be a bit like phone calling. I don’t know about you, but I no longer pick up any phone call from a number I don’t have registered due to the sheer amount of random scammers calling me. So in the phone-calling ecosystem, the erosion of trust has led to a fenced off system, where in order to communicate with another user you first need to know that persons identity: its phone number. In this setting, we’ve pretty much given away anonymity in favour of trust, and it is not far-fetched to think that the Internet may end up in a similar place. If we don’t stop the whole of the content on the Internet becoming of dubious nature, if the line between genuine interaction and bots gets blurred and the content can no longer be trusted, people will either abandon it entirely, or seek refuge in pockets where identity can be trusted (e.g. Whatsapp).

The disinformation explosion

With the (dis)information explosion provided by the Internet, we went from “knowledge is power” to “knowing what to filter is power”. Arguably, because all sorts of information became so widely accessible, critical thinking and the ability to reliably source information became as (if not more) important than knowledge itself. But we are entering an era in which the capacity to “know what to filter” is being eroded. If distilling the truth is already difficult in recent events (for instance when Russia blames Ukraine for certain actions, which Ukrainians deny taking part in), what will happen as these algorithms get more sophisticated, as you can no longer trust the content you see, the comments you read, the profiles you interact with? My guess is that either we fix the Internet really soon, or the lack of trust will turn into an automaton de-voided of any human presence.

Written by a human.

You’ll also love this one: TikTokfication I: an AI-driven Idiocracy (when AI gets better at distraction)

Leave a comment